Here comes . . .

There goes . . . Chi Coltrane . .

by Richard Boeth

This is all about the possible rise of a rock singer

named Chi Coltrane, but we need a little background music first....

Whenever I think upon popular American heroes, I

never fail to cast the mind back to the fighter pilots of World War

II - authentic folk idols they were, ever ready to fly their Birds

of Paradise up the other guy's nose if it meant a few less Nips for

Uncle Sammy to have to worry about. Since then, it seems, we have

got to the point where almost all our pop heroes have something

basic in common with World War II fighter pilots-one brief but glorious

arc across the sky as the whole nation cheers, then phooom and

on to the next folk hero. Andy Warhol, in his ghostly way,

caught the essence of it when he remarked that in the next generation,

everybody in the whole world is going to be famous-for five minutes.

Until that era arrives, we have a pretty good approximation

of it in the institution of the rock star. I don't refer here to

the neighborhood rock star, earning $100 a weekend at the

Dew Drop Inn and wondering where to send that demonstration record

he made last month in somebody's basement. I was thinking of the

thousand more or less professional groups and singles that have come

and gone in the last decade. They played for $2,000 or so a night-

superloud, derivative electronic whingwhang with too much past and

no future-warming up the concert crowds for Sly and the Family Stone

or Poco, and maybe putting out one album on Buddah Records, plus

a hit single that reached number eighty-seven on the charts. These

near-miss groups got a very brief, very dizzy ride for their pains.

One minute the air was thick with grass and adulation; they rode

limos to the airport with groupies in the glove compartment and a

tax man riding shotgun trying to help them figure out where last

year's $200,000 went. The next minute everything was gone (it wasn't

really there to begin with, of course), and the lead singer

was back driving a taxi in Detroit and dreaming of the second big

break that would almost surely never come.

There is a big dream behind it all, however-and it

is this large economy-size job that keeps the whole carnival spinning.

Every knock- kneed banjo player, every mudcolored group catastrophe,

has visions of becoming the rock trade's newest Messiah: the He,

She or It who will turn out to be another true superstar,

someone who will bridge the great divide between rock and pop and

will go on selling records, year after year and million after million.

Presley, the Beatles, Dylan, the Stones, now maybe James Taylor,

Carole King, Cat Stevens-all these performers were and are true superstars,

true perennials, arners of legitimate bankable millions in their

own right and of millions more for all those record companies, electronics

manufacturers, rack jobbers, and simple unassuming ticket-scalpers

who work the Felt Forum and the Portland Auditorium. Where will we

find their like again?

Where, indeed? Actually, the superstars are hardly

monuments to permanence themselves (always excepting Presley). Hendrix,

Joplin and Morrison are dead, the Beatles have split up, and while

it may be too early to predict just when the string will run out

on the rest, it doesn't seem unfair to say that rock superstars have

a natural performing life of a decade or less. That's enough, really.

The economics of the music business today are such that Dylan can

make more money in five years than Duke Ellington has in fifty-so

five colossal years count as a whole career now, and the

record companies are constantly on the prowl for anyone with any

sort of potential for making it into orbit that long. So it's a fascinating

and elusive chase, made up in about equal parts of hard show-biz

professionalism and soft, dreamy-eyed divination and wishful thinking.

The odds are enormously against anyone's making it all the

way to the top rung, but the rewards are so huge up there that the

performers and the record companies alike can't resist taking an

expensive crack at it whenever the slightest plausible long shot

presents itself. So here, for your edification, is the story of one

Plausible Long Shot: a pop-rock singer still only in the larval stage,

promotionally speaking, but one who has been picked out for the big

push by Columbia Records, which has a track record of pouring more

money, determination and know-how into these cosmic creations than

anyone in the business. And still the odds are enormous

that our heroine won't be any more of a household name a year from

now than she is today. What makes it fun is the other possibility,

the one- in-a-million chance that by the time you read this our heroine

will be rubbing royalties with Melanie and Laura Nyro-or maybe even

with Carly Simon and Carole King. Ready, set, go.

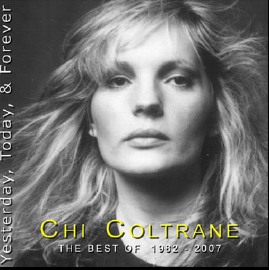

She is called Chi Coltrane,

and she wants it known that this is her real name, so why not?

The Chi is pronounced "shy," the

Coltrane is no relation to the great jazzman John Coltrane, and it

is possible that you have heard of her already. Her first album,

which came out in the spring of 1972, sold something close to 100,000

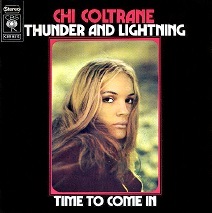

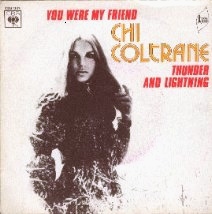

copies (and we shall have more to say on this in a moment). One single

derived from that album, a driving, up-tempo member called "Thunder

and Lightning," reached member thirteen on the national charts

that summer, selling about 500,000 copies overall, and in a few cities

such as Boston and Chicago it was one of the biggest hits of the

season.

Chi is an honest twenty-five now (she usually knocks

a couple of years off her age out of fear that the teen-agers, who

are every rock musician's lodestar, will have more trouble relating

to an older woman), and she is in every way a splendid singer person:

smart, gifted, determined, pretty, ballsy, and very good at what

she does. What she does is play half a dozen musical instruments,

preeminently a piano from which she coaxes everything from piano-bar

kitsch to funky back-alley blues, and sings. Her songs cut across

a similar range: reedy little Carole King-like laments, whammy up-tempo

revival numbers, earnest and well-meant blues that just don't have

enough sex in them to warrant comparison with Joplin (much less Nina

Simone) but that sound pretty good in comparison to a nice sweet

thing like, say, Carly Simon. Chi writes all her own material, too.

Shez didn't use to, not until a couple of years ago, but then she

figured out that all the really big rock stars write their

owns songs. Anything the big girls do, Chi figures she can do, too.

It would seem from all these

qualifications that Chi is pretty well set. She has talent, experience,

one well-received if not quite sensational album already on the

market and another aborning. Best of all, she boasts the standard

one plus-four recording contract with Columbia - meaning that Columbia

promises to bring out one Coltrane LP in the first year of their

association (as it has already done), with the option to renew

each year for four more years. Chi's option for the second year

has already been picked up, and Columbia remains genuinely and

all but irrepressibly excited about her future. Too many people

believe in Chi for her to have much chance of failing-everybody

from Clive Davis, [then] company president, on down," says Bob

Altschuler, Columbia's publicity chief but not a wholly irresponsible

source of information for all that. "It's overwhelming, it's

all one-sided. Everybody thinks she's going to be the next

real superstar." And this could be the truth.

So what is this girl's problem'? Why is all the talk

about Chi's future when it would seem to any casual observer

that she is doing pretty well right now? Answers in a moment, but

first let me bolster the illusion of her present success even further.

Just from her first album- with its hit single, "Thunder and

Lightning" - Chi would seem to have pulled in enough money to

keep anyone but a glutton in truffles, for a few months, anyway.

Under her contract with Columbia, she earns about forty-five cents

from every LP as a performer, plus another twenty cents as composer-

a total of almost $60,000 if we figure on a conservative basis of

ninety thousand albums sold. The single brought her a nickel a record-add

another $25,000. Then there were air-plays; as composer of " "Thunder

and Lightning," she received two cents every time the song was

played on a commercial radio station in this country. Figure six

plays a day on 3.600 radio stations for the four weeks the record

was hot, and that comes to another $12,000 or so, making for a grand

total (flourish of trumpets) of about $85.000, not counting the $21,000

that Columbia, a talent agency, and various clubs threw in last August

to underwrite a promotional tour.

That's not bad bread, or at

least it wouldn't be if it were real. But the truth is that Chi

is living in a $200-a-month apartment in West Hollywood, on the

unfashionable side of the Sunset Strip. She drives a battered heap

in place of the white Lincoln Continental she once had in Chicago

(it got totaled by an oil truck), and the mink coat once shimmering

in the closet has long since been sold to pay the rent. All the

money from her records has gone to pay off various necessary advances

from Columbia, and she is tens of thousands of dollars "in debt" to the record company, various lawyers,

agents, managers and arrangers. It's impossible to put a hard figure

on Chi's "indebtedness," because much of it is as illusory

as her wealth, that is. Various people and companies have advanced

her all kinds of services, facilities and expertise in the expectation

that she will someday make it big. If she does, she pays them off;

if not, or if she drops out to join a Nepalese nunnery, everyone's

all square. In the meantime, though, Chi literally struggles along

close to flat - broke on what looks at first glance like an "income" of

better than $100,000 a year but is, he truth, a fraction of that.

What she actually lived on for the last five months of 1972 was $3,000

carefully saved from her promotional tour.

To understand how this very appealing girl got into

this perfectly typical fix (typical for a young recording artist,

anyway), we had better double back to the thrilling days of yesteryear

when Chi was trying to hack it as a sometime saloon pianist, sometime

hard-rock bandleader in Chicago. This would have been the late summer

of 1971, and things were both good and bad for Chi. She had spent

the year before pouring most of her money, energy and soul into trying

to make a go of her own band, known (naturally) as Chi Coltrane,

and had come out of the experience weary, broke and sort of brittle

- the state of mind in which you think you are tough as hell but

you're really ready to crack the minute somebody taps on you. Add

to the saga an unsuccessful marriage that had finally ended after

four draggy years - that was a help. She had also been picked to

represent the U.S. at an international rock festival in Rio (Elton

John had been U.S. representative the year before), and that was

good. Chi was also working regularly in such places as the Executive

House and the Back End in Chicago, but the long- range career didn't

seem to have many mountaintops in its future, and Chi was perhaps

a little more receptive than she should have been when a Chicago

theatrical personage told her he had the contacts to put her into

records and concerts-otherwise known as The Big Time. Chi signed

him on as her personal manager, then began discovering, she says,

that his contacts weren't quite the right sort. "He knew a lot

of actors and actresses," she says, but that didn't help me." Her

new manager did persuade her to move to the West Coast, however,

and she booked herself into a couple of pretty good clubs and wangled

some guest shots on national TV, notably on the Merv Griffin show.

What she needed, however, was a record contract, and that still wasn't

forthcoming. So Chi took on another partner, an able and

knowledgeable independent record producer named Mike Gruber, and

with him formed Just Us Productions, whose sole purpose was to package

and peddle Chi Coltrane to a big record company.

That, as it turned out, was

a fairly easy thing to do. Chi had been writing material for some

months, and had six songs ready to go; using just bass, drums and

a guitar for background, and spending little more than $1,000,

Chi and Gruber produced a demonstration tape with six songs on

it. Gruber then called Paul Baratta, a veteran Artists and Repertoire

executive at Columbia's Los Angeles office, and said, "I have a tape of Chi Coltrane's, and I think she's

going to be a superstar." Veteran A&R men are supposed to

be skeptical, but Baratta evidently didn't take much persuading.

An oldtime theatrical casting agent, he tends to judge people by

how they move. When he saw Chi walk into his office-all

chunky hard-packed energy, with that pretty blond head riding above

- he instantly became the mentor, guide and champion she had been

looking for ever since she started singing for nickels and dimes

in Zion, Illinois, seven years earlier. "Even before I heard

anything,'' Baratta told me, "I thought she was the most emotion-filled

talent I'd ever felt." The demo nailed it. Baratta immediately

called Clive Davis at executive headquarters in New York and insisted

on fetching Chi with him to meet Davis. "Davis would have gone

along just on my faith." Baratta says, "but I wanted him

to be involved."

Chi went to New York, conquered

Davis, and went back out to the Coast to cut her first record in

February of 1972. An uptown production using nine first-rate sidemen

and a chorus; the eleven tunes took two weeks to record, with everybody

working ten six-hour sessions, and then three weeks on top of that

to do the "mixing" (the

balancing and blending of song and rhythm tracks, and in this case

the addition electronically of occasional horn or string backgrounds).

When it was done, Chi sent the master tape to New York, where the

ponderous machinery of Columbia's marketing and promotion departments

groaned into action. In all, about fifty different executives and

department heads crowded into Clive Davis's office to listen to the

master tape (for most of them, it was the first time they had heard

their latest phenom). Preliminary decisions were made about which

songs might go best as singles. Chi herself-who had done everything

from writing arrangements to booking hotel space in her knockabout

musical career-flew into New York again and made herself known and

agreeable to all the key hands, including the executives in charge

of A&R, marketing, artist relations, publicity, cover design,

the lot. About $10,000 was budgeted for ads, mostly in trade publications:

a free-lance West Coast publicity outfit was signed on to do additional

tub-thumping at $800 a week: a three- month tour was laid on for

Chi and a backup group in Denver, San Francisco, Boston, Chicago,

New York, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, Washington (D.C.), Los Angeles

and Ipswich (Massachusetts).

Chi now calls the tour "the hardest thing I've

ever done in my life." Daddy Columbia had included a road manager

in the traveling carnival, but Chi's years in the back alleys of

the music business had left her with the feeling-which she still

has, to the eye-rolling annoyance of some of the people who work

with her-that nothing will ever get done unless she does it. "I

put together the group, made air and hotel reservations, paid the

bills, handled the phone calls, talked to writers and deejays, and

rented the trucks for the sound equipment," Chi told me at lunch

in New York recently. "There were supposed to be two guys doubling

up in each of two hotel rooms, and me in a single. But two of them

were clean livers and two were swingers. The swingers wanted a room

of their own, so I ended up sleeping on a cot with the two clean

livers while the swingers got room to play."

The purpose of the tour, of

course, was not simply to introduce Chi to new club audiences but

to reach the disc jockeys, who for the most part were tranquilly

unaware of her existence. The ultimate object was what Altschuler

calls "the single hardest

thing in the whole world-getting airplay."

Whether it was the tour, Columbia's

promotion efforts, the merit of the album itself, including the

now-released single of "Thunder and Lightning," whatever

was most responsible for turning the trick, Chi did begin

to get her precious air-play soon after her tour began in May.

Boston was the first city to go for her in a big way: the disc

jockeys in Chicago picked her up a little later (without knowing

what was happening in Boston), and several other key areas followed.

New York didn't join the group. Despite a big ride on WCBS-FM, "Thunder and Lightning" was

never a major wow in New York, a provincial town, musically speaking,

which generally doesn't catch on to a new singer until all the rest

of the world has caught on first. Still, the single made it up to

number thirteen nationwide one week, a performance that, for a newcomer,

ranks somewhere between sensational and dynamite.

All these happy successes represent the rosy side

of the saga of the Plausible Long-Shot. What I've left out so far,

in the interests of narrative clarity and suspense, is the fact that

Chi Coltrane during this period of her glamorous emergence into the

big time was as hassled and frightened as a chick can be -and, if

anything, getting poorer by the minute. The economics of the record

business is made up of some dazzling high-energy numbers, but these

very rarely break down to the immediate enrichment of the performer.

The largest worm in the apple

is that all recording artists pay the production costs on their

own records-or "borrow" them,

as is more likely, as an advance from the record company. Chi's first

LP was not an extravagant production, but it was well and carefully

done, with good musicians and technical equipment and no corners

cut in the studio. The result was that the record cost Columbia something

close to $100,000 to produce, all of which went down in the little

black ledger to be deducted from Chi's royalties as they came in.

As we saw earlier, Chi has earned about $60,000 from the LP so far

on sales of about ninety thousand copies-so she still owes the record

company something like $40,000 just to get off the nut on her first

LP. This may or may not be unfair, but is certainly standard practice:

Paul Baratta told me that a performer has to figure on selling about

175,000 LPs and perhaps half a million singles before he, she or

it begins to show a net plus.

The record company itself is not in so tough a bind.

Though Columbia pays promotional and marketing expenses out of its

own pocket, it still figures to net close to a dollar on the $3 wholesale

price of a pop or rock LP. What this means is that the record company-unlike

the performer-breaks even on LP sales of about fifty thousand, so

Columbia made out all right on Chi's first album.

In Chi's case, the financial picture was a good deal

worse even than we've seen so far. All the figures about royalties

up to this point have been given as if these earnings went wholly

to Chi-which they rather spectacularly did not. By the time she had

finished signing up with her personal agent in Chicago-she is still

bound to him in some mysterious legal way and Mike Gruber and Just

Us Productions in Los Angeles, Chi had managed to divest herself

of something more than 50 percent of her own earnings, often in fairly

complicated ways. All her music, for example, was copyrighted and

published under the name Chinick Music-a partnership between her

and her original manager. So there went half of her composer's royalties

right there, and it would not have been unusual (though I do not

know that was the case here) for her manager to have taken about

- 25 percent of her half of these royalties as a fee for

personal services. Just Us Productions, which is to say Mike Gruber,

also came in for a percentage of her earnings off the top, and there

were a hundred other hidden costs for a neophyte to hang up against.

An arranger named Toxey French made a few suggestions during the

cutting of Chi's LP (almost none of them were used, she says) and

submitted a bill for $1,800. This was not out of the ordinary in

any way, but Chi still feels that she was booby-trapped. "Toxey

didn't rip me off," she said. My own inexperience ripped me

off." All in all, Chi was cut up so many ways that her nominal

earnings of $100,000 in 1972 really came down to less than a half

of that - and every penny of what she did make was spoken

for before she properly got her hands on it, anyway. Chi has now

hired some good lawyers (high-priced ones) to try to negotiate her

way out of this mess with all her managers and agents but the likelihood

is that she is going to have to be very rich indeed before she stops

being poor.

What keeps this story from being an all-out tear-jerker

is the internal evidence that Chi may well have survived too much

for too long to let anything stop her when she is this close

to cashing in big. She grew up grubby-poor in the rundown factory

town of Racine, Wisconsin, one of seven children in a family so rootless

that Chi attended twelve different grade schools in eight years.

Music was her one salvation. She learned to play about eight instruments

by ear, the piano supreme among them, and took her early influences

where she found them - Strauss waltzes, Stephen Foster, even Liberace

on the tiny tube. Leaving at seventeen she began singing weekends,

just for kicks, with bands in small clubs just across the state line

in Illinois. More out of boredom than anything else, she began working

a few little clubs in Chicago about five years ago. From the start,

she had a sort of schizophrenic career. Part of the time she spent

singing rock, blues and gospel with black bands in out-of-the-way

joints in Chicago; part of the time she spent hired out (at about

$300 a week) to genteel cocktail bars, playing piano and crooning. "The

piano bars were a drag," she says. But the money was good there,

and she stayed at it at least part-time until the summer of 1970.

Chi's subsequent attempts to make it as a rock star- first with her

band, and then later as a solo performer-not only took most of her

assets but also most of what was left of her trust in her fellow

man. It is perhaps not irrelevant that she became a Jesus freak in

those dark days-and still is, though she doesn't talk about it much

except among other JFs. Christian fellowship provides her only deep

human contact: she has little to do with guys, singular or plural,

and has no real friends, except maybe for Columbia's avuncular Paul

Baratta and his wife.

But soon the college and concert dates and the touring

will resume, with Columbia Records doing its part by ferrying

in disc jockeys, wholesalers, newspaper reviewers, and everyone else

in the business to listen to the new sensation. By that time, the

new LP will be out, and Chi will have passed one more milestone on

the rock star's road to success. What milestone? Why, Chi Coltrane

will be another $100,000 or so in the hole, and that's the surest

sign of stardom there is.

![]()

![]()